- Home

- Technology

- Management

- Health Care

- Earth Sciences

- Particle Physics

- Engineering

- Stories of Turtle Island

- Startup Companies

- The Lost Ships of the Franklin Expedition

- Wildlife

- Archaeology

- Palaeontology

- Architecture, Land Use and Planning

- Politics and International Development

- COVID-19

- University Life

Isotope analysis shows earliest known dairy production in IndiaIn the fertile river valley along the border of modern-day India and Pakistan, the Indus Valley Civilization built some of the largest cities in the ancient world. Feeding such a large population would have been a significant challenge. Research from Kalyan Sekhar Chakraborty reveals one of the ways the civilization was able to sustain so many people. The postdoctoral researcher at the University of Toronto Mississauga has shown that dairy was being produced as far back as 2500 BCE. It is the earliest known dairy production in India, and could have helped produce the type of food surplus needed for trade.

Click here for full text |

Indigenous people raised alpacas in Atacama prior to Spanish contactIndigenous people were raising alpacas and llamas in the Atacama Desert to make textiles prior to Spanish colonization of the region.

Alpacas and llamas were the only species of large mammal that was domesticated in the Americas, prior to European colonization. They are closely associated with high mountain plains environments, and it has long been assumed they were only raised there. Remains of llamas and alpacas from other parts of South America identified by archaeologists were believed to have arrived by trade or other means. Click here for full text |

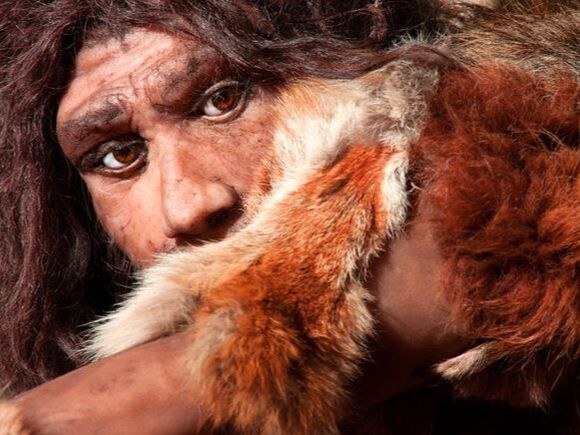

Neanderthals used sophisticated techniques to hunt small gameFleet of foot and lean of meat, rabbits are difficult to hunt and offer little sustenance. Yet research published in Science Advances, Dr. Eugene Morin has shown that they were frequently part of the diet of early humans and Neanderthals in the northwestern Mediterranean as far back as 400, 000 years ago.

Morin and Jacqueline Meier examined rabbit bone assemblages from eight Lower and Middle Paleolithic sites in present-day France, including Terra Amata, an open air site near Nice where they collected rabbit bone assemblage data. Click here for full text |

Neanderthals adapted hunting techniques to changing climateLong before the rise of ancient Greece, Europe was a continent of hunter-gatherers. For hundreds of thousands of years, they used stone tools and hunted large game like European bison and reindeer, but Dr. Eugène Morin has shown that they hunted smaller animals like rabbits too.

Hunting small, difficult to catch animals means that Neanderthals had broader diets and were more concerned with efficiency than they’re usually given credit for. “In some ways, we feel we're close to them. In other ways, we don't feel that close. My research reassesses assumptions about their cognitive abilities. I want to see whether their behaviours are consistent with those of contemporary hunter-gatherers, and also how they differ.” Click here for full text |

Passenger pigeon extinction caused by hunting, not habitat lossThey once numbered in the billions, and travelled in flocks so large they blocked the sun for days. But in 1914, the last of the passenger pigeons died at the Cincinnati Zoo.

Passenger pigeons were a staple of the North American diet in the 19th century and were easy to hunt, especially after the telegraph made it easier to locate enormous pigeon flocks, and railroads made it easier to ship their meat to growing cities. But was overhunting what killed the passenger pigeon? It is one of two prevailing theories on how this once-abundant species declined to extinction in a mere 40 years. Habitat loss has also been considered as a possible cause its decline. Click here for full text |

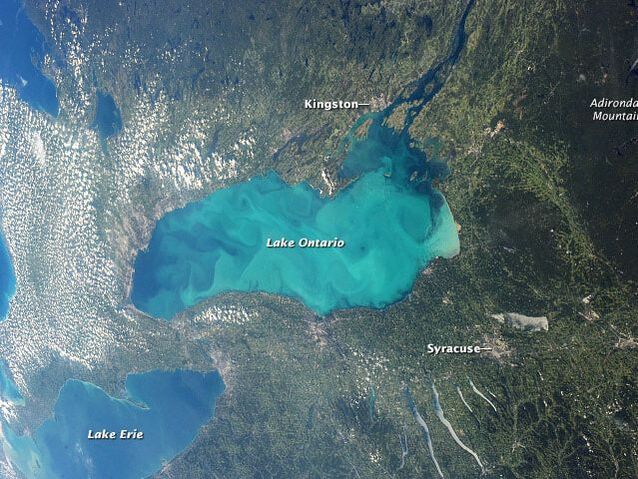

19th century logging and farming changed chemistry of Lake OntarioChanges in logging and land management practices in the 19th century caused a profound ecological shift in one of the world’s largest freshwater ecosystems.

Nitrogen levels in Lake Ontario increased as a result of widespread deforestation across its watershed after at least 800 years of relatively stable levels. The new research shows this balance suddenly shifted when forests were cleared, the land became more vulnerable to erosion, and nitrogen-rich soils washed into the lake. “Shifting a lake’s nutrient balance, of which nitrogen is a key component, can have significant effects on the health of the plants and animals that live within it,” says Dr. Eric Guiry. Click here for full text |