- Home

- Technology

- Management

- Health Care

- Earth Sciences

- Particle Physics

- Engineering

- Stories of Turtle Island

- Startup Companies

- The Lost Ships of the Franklin Expedition

- Wildlife

- Archaeology

- Palaeontology

- Architecture, Land Use and Planning

- Politics and International Development

- COVID-19

- University Life

Drones and artificial intelligence enable aerial surveys of bird populations in remote areasThe Morris Island Conservation Area is only about an hour’s drive west of Ottawa, but on a brilliant autumn morning, the city feels a world away.

The 47-hectare mix of forested woodlands and wetlands is bursting with crimson and gold, with reflections of towering maples and a cloudless sky shimmering in the glassy back bays of the Ottawa River. And even though it doesn’t look the part, Morris Island is a stand-in today for distant James Bay, which stretches south from Hudson Bay about 1,000 kilometres north of the National Capital Region. Backed by low-lying marshland, James Bay is sparsely populated and lined with broad beaches and nutrient-rich mudflats. It’s an ideal place for more than two dozen species of shorebirds to rest and feed before they continue their epic migrations. Click here for full story |

Genetic analysis builds understanding of fish migration patterns beneath Arctic sea iceCanada’s coastline is 243,042 kilometres long — far longer than that of any other country. If you stretched out the shoreline of every island and inlet, it would wrap around the equator six times over.

Tracking the fish that live along these shorelines – and swim up rivers that flow through them — is far from simple. It’s especially difficult in the Arctic, where vast distances, low population density and winter ice cover combine to make it difficult to understand exactly where fish are coming from and where they go. “Arctic fishes remain somewhat mysterious compared to those in the south,” says Jacqueline Chapman, who is researching fisheries in northern Canada as part of the FISHES project, short for Fostering Indigenous Small-scale fisheries for Health, Economy, and food Security. Click here for full text |

Jumbo squid enter state of suspended animation in the deep Pacific OceanDeep in the Pacific, against a backdrop of liquid darkness, a virtual armada of jumbo squid lay in wait. More than 1,000 strong, they bob in a state of suspended animation hundreds of metres below the surface. Once night sets in, more than 1,000 will ascend to the surface for a feeding frenzy and ravenously devour their prey.

And the prey? That can even include humans if they’re in the wrong place at the wrong time. A school of jumbo squid is more frightening than a Sharknado, and it’s mostly because they’re an actual thing. In Mexico, fishermen nicknamed them “diablo rojo” – the red devil. They’ve attacked submarines and scuba divers. Fishermen who are unfortunate enough to fall into squid-infested waters sometimes never emerge. Click here for full text |

Hybrid species like coywolf hold clues to human evolution

The offspring of two horses will be a horse, and the offspring of two donkeys will be a donkey. But the offspring of a horse and a donkey will be a mule. And most mules are infertile, so mules are not a species.

For decades, this was the basic logic used to define a biological species. It is a population of animals that can successfully reproduce. But that definition is shifting. There are hybrid animals that produce fertile offspring, and grow into larger populations, but are not necessarily their own species... Click here for full text |

Natural and cultural evolution shaped humansFrom a single-celled organism in the distant past, life evolved into an array of species so diverse they defy superlatives.

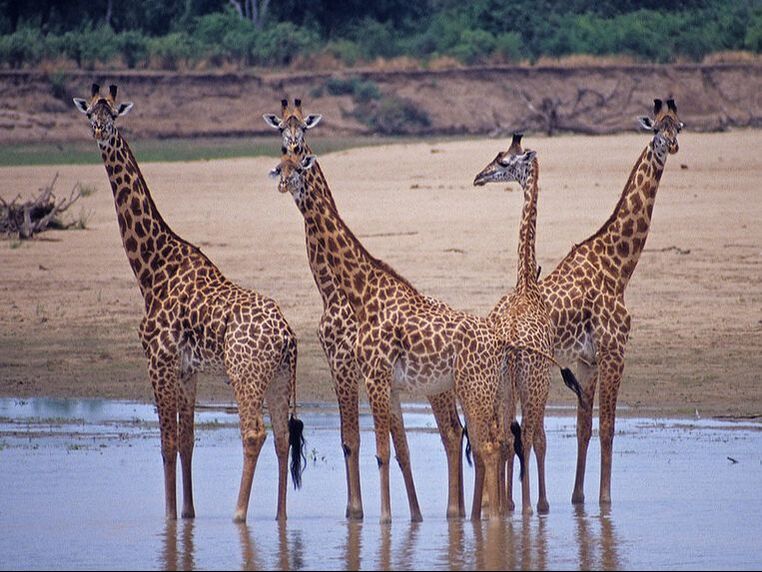

Unique adaptations gave species an advantage – the superior fitness to fill an ecological niche. There are about 4,000 species of mammals – towering giraffes nibble on acacia leaves out of reach for other animals, and the wings of the albatross carry it to the Pacific’s most remote fishing grounds. Click here for full text |

Snow goose overgrazing destroys shorebird habitat in arcticYou’re not imagining it. There are more geese than there used to be. Way more.

Lesser snow goose populations have ballooned by 700%, from as few as 2-3 million in the 1970s to about 16 million today. Geese are herbivores, and thrive on a diet of corn, rice, and wheat – all of which are widely available to geese improved agricultural practices in the southern United States. Farms sprawl across the continent, and the abundance of food they provide has caused a population explosion. Click here for full text |

Guggenheim Fellowship will help researcher interrogate contiguous habitat conservation orthodoxyA drone hovers above the treetops to capture the endless sweep of a seemingly pristine forest – a sylvan sea that’s home to creatures great and small. It’s the kind of scene that’s at the centre of BBC nature documentaries, but are large, contiguous conservation areas like this actually the best way to conserve biodiversity?

For decades, there has been an orthodoxy in conservation biology – large, contiguous tracts of land are better for biodiversity than multiple, smaller parcels that add up to the same size. But that assumption relies on logic, and not evidence. “My research has shown that it is not actually true,” says Dr. Lenore Fahrig. Click here for full text |

Global Urban Evolution project demonstrates parallel evolution in cities around the worldHumans are constantly re-shaping the environment by building sprawling cities, but a new study demonstrates that urban environments are also altering the way life itself evolves – and it’s happening all around the world.

“We’ve long known that we’ve changed cities in pretty profound ways and we’ve dramatically altered the environment and ecosystems,” says study co-lead James Santangelo, whose research was published in the journal Science. “But we just showed [the reverse] happens, often in similar ways, on a global scale.” Click here for full text |

Nature sounds shown to alleviate stress and improve cognitive performanceIt’s in the way that waves lap at a beach and the call of a loon echoing across a lake. It’s in grasslands that rustle in a prairie breeze and the chirping of songbirds in a wetland. When people imagine nature, they often imagine a visual, but every landscape has a soundscape and those sounds are good for human health.

“Natural sounds alleviate stress and provide a range of health benefits, says Rachel Buxton, a research scientist. "They improve our mood and cognitive abilities. They have been shown to decrease pain during painful medical procedures and, of course, they alleviate stress.” Click here for full text |

Citizen scientists monitor re-introduced wild turkeysThere were no wild turkeys in Ontario for the better part of a century. The species was extirpated in 1909, but in the early ’80s, they were successfully reintroduced.

Now, they are abundant in parts of the province with a total population of more than 70,000. However, their success story is not quite that straightforward. Previous attempts to reintroduce the species failed. They disappeared after just a few years, as they failed to survive in human-altered landscapes. Click here for full text |

Breeding program revitalizes Aurora troutIn the 1920s, scientists identified aurora trout as a new species native only to northeastern Ontario. Their habitat stood squarely in the path of emissions from Sudbury’s giant mines, and aurora trout became an early victim of acid rain. Populations went into steep decline by the 1950s.

To save the species, Government of Ontario biologists captured every adult fish they could find – three females and six males – and raised the next generation at a local hatchery. Every aurora trout alive today is descended from those fish. Click here for full text |

Ultrasonic recording enables monitoring of flying squirrelsThe northern flying squirrel lives in every province in Canada, but this nocturnal creature is rarely seen – or heard. During the day, flying squirrels stay hidden away in their nests in tree cavities, but when night falls, they emerge to glide silently between the branches.

Or at least they seem silent to us. Northern flying squirrels communicate via ultrasonic calls that are so high-pitched they are not audible to the human ear. Click here for full text |